Reading Isn't Just Fun

It's Fundamentally Broken

It’s 8 in the morning, and I’m sat in the wind, waiting for the bus. It’s cold, but not too cold to be outside. I look up, see clouds, and smile. Rain. I just picked up groceries for dinner, and I know I have about twenty minutes left before the bus comes, so I start to listen to an episode of my favorite podcast, The Yard. In this episode, sandwiched between the self-admission that podcast host Ludwig from Video Games hung out with nine-year-olds and the boys collectively learning about the concept of Australasia, was an off-hand comment from host Slime, who brought up a change in the way reading is taught to kids as told to him from a teacher. This exchange, occupying less than a minute of a podcast, was my Reading Rainbow activation phrase. Damn. Are kids getting dumber?

Caption: “The Yard(tm) Child Pageant for K-12 Literacy (Adults Only)”

But how? Why?

I’m just a humble college drop-out, but my field of study was education-oriented, more on the technical side of learning to read and speak. I studied linguistics and how our brains form thoughts that may some day grow up to be a written confession of true love, or a thoughtfully slurred conversation in your Uber home from the bar. This field of study does not really prepare you to answer either of these questions with much certainty. I can tell you the bad news, pull out all of the graphs and calculations and cross-analysis at my disposal that suggests that the paperweight on my desk can read better than your child, but not why that happened. I could do years of research and write an article about how to properly teach, but if these methods are never implemented then they exist only in theory.

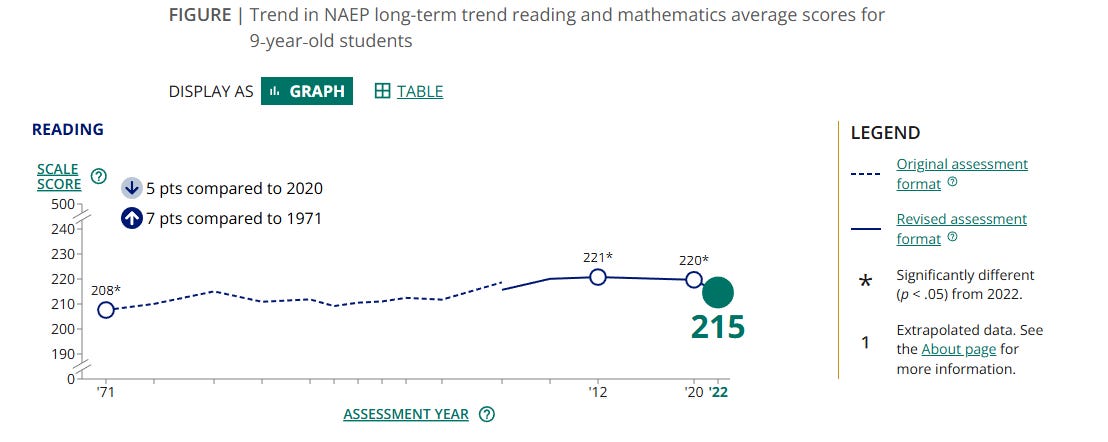

To look back at my time spent in school, shoutout to the graduating class of 2015, we first had No Child Left Behind (NCLB) in 2002. NCLB was negatively received by teachers, but on the bright side, it’s given at least one student in America a fetish for scantrons. In order to get a better idea of whether it was good or bad at a glance, take a look at the graph below:

What you are looking at is a graph of 9-year-old reading scores put out by the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). It is an annual program that assesses student progress in reading and math, but other subjects as well. The reading levels of these students were already on the rise before NCLB. This is shown in the grey dotted line, the end-point of which is 2002, when the NAEP standards and materials were modernized for a new generation of students. This predates NCLB. This also changed the scoring system, resulting in the visible gap between dotted and solid lines, but the student average still trends upwards. No clear sign of change, at least not that can be attributed to NCLB. Sorry, Bush. NCLB was later replaced by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), in 2015. ESSA is often associated with the new Common Core State Standards (CCSS), much adored by conservative pundits and candidates alike. The curriculum behind CCSS is very much informed by the requirements that drive ESSA, although its adoption is not a requirement; states may choose different curriculum, so long as they still assess their students’ progress by ESSA guidelines.

While NCLB, ESSA, and CCSS deserves its own discussion, and it will receive one, it’s important to mention a few key points now. NCLB was an accountability-based system, where programs were in some way directly responsible for the outcomes of their students; if your school’s academic performance fell so, too, did their funding. While there were some leniencies, particularly when it came to schools in low income areas, it was not a perfect system. ESSA was a strong step forward. It shortened the stick (although not removing it entirely), and is also not a perfect system. It pared down what requirements there were under NCLB but is still, at its core, an accountability program for schools, and the threat of losing federal funds looms overhead. This trimming of the stick, joined with Common Core, has had some negative repercussions in "non-targeted" areas:

We find a significant negative effect of the CCSS on student achievement in nontargeted subjects. More specifically, being exposed to the CCSS for the entire school career (at the time of testing) as opposed to not being exposed to the CCSS at all decreases student achievement in non-targeted subjects on average by 0.08 units of a standard deviation. The effect size can be interpreted as a loss of learning worth approximately 25 percent to 30 percent of a school year. (Source linked above)

The performance requirements of ESSA pushes a hard-lined focus on reading and math, but leaves subjects like the sciences and humanities by the wayside.

However, despite its current failings in other subjects, it's hard to pin the decline in reading ability solely on Common Core. Between 2012 and 2020, the average declined by one point. While you could say it’s due to a change in curriculum, other causes range from teachers adapting to new materials, to students adapting to a change in tests, both of which would take time to shake out. This is put further into question by the notion that, if it was due to Common Core, then it would only be a decline in the states which have adopted it, not nation-wide. For now, we can assume that Common Core did have something to do with the decline between 2012 and 2020. But, what it does not explain is the plummet that occurs after 2020.

So, quarantine made kids dumb? Great.

Not quite true, either. Quarantine was not a pleasant span of time for many people, when the lockdown deprived us of simple luxuries such as being able to pass off a headache or cough as “something that will pass,” or being able to look at neighbors in the eyes when they pass by, and this is especially true for students and teachers.

Zoom school sucked, by all accounts, for all ages. I was still in college when the lockdown occurred, and while doing my linguistics homework after a long day at the liquor-drinking factory was fun a few times, I don’t think it was worth the trouble. I was late to class for the first time in my academic life, an odd thing to say considering I was about 15ft away from my desk at any given time. I also, at points, just fell off the face of the earth. I feel as though I’m preaching to the choir here, but there was something uniquely exhausting about sitting down, staring at a screen, only for class to end and just… staying there. And I'm a shut-in, by all accounts!

As for students in K-12, kids and teenagers who didn't have the room, let alone the skills, to separate school, work, and life when they are all contained in one space, or who lived in households that were not suitable to serve as classrooms, lockdown was significantly worse.

POV: You’re a successful junior in college with a bright future ahead of you.

I think it’s right to say that quarantine definitely deprived people of an education. The social element of education is equally important to the material being taught, and many were deprived of this in a pivotal moment of their lives. The good news, though, is we’ve never been so back! Quarantine is over! Grocery stores! Concerts! Breathing all over your neighbors and in their open mouths and eyes and noses!!! Surely, outcomes are going to improve.

Caption: Nope.

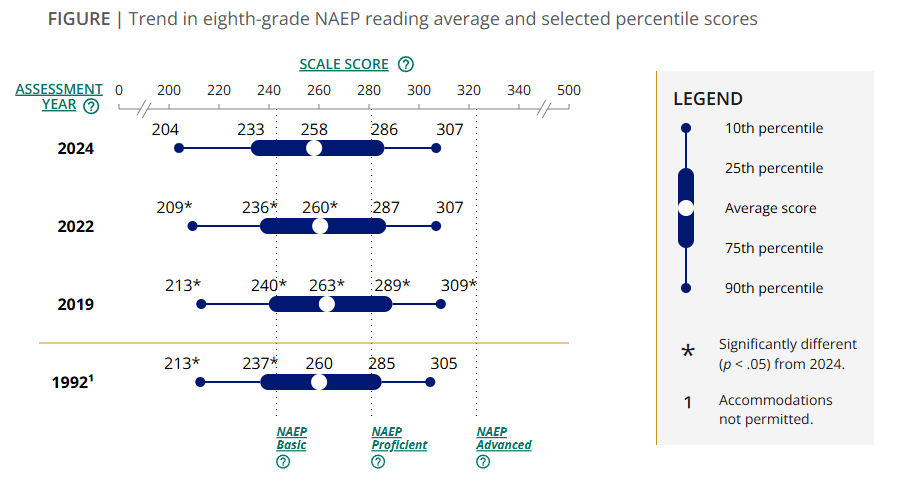

This is a box-and-whisker plot. You find your average scaled score, then the “box” encompasses all data outside of the highest 25% and lowest 25%. This, then, makes up where the majority of students scored. The “whiskers” account for most of the data outside of these quartile ranges. I was not sure if I needed to explain this, but then I decided to explain how it works to myself, as a fun and flirty exercise, and did a lot of “*hand gestures* you know???”-type explanations. It's also important to explain the function of a plot because it exfoliates some underlying problems.

I would not blame you if you took a look at this graph and said “Well, some amount of this is due to compounding failure. Students did poorly in quarantine, and that is now impacting their ability to do well in future grades today, in ‘normal’ times.” I also think it’s perfectly fair and reasonable to look at this graph and make noises that don’t register to the human ear. What stands out to me is that the lowest-performing and highest-performing ranges on the plots are very consistent. When you track these scores to their respective populations, you find that it ties to socioeconomic inequalities in education, most recently exacerbated by acts of congress like the ESSA.

We won’t know if this is truly as much of a decline as it looks until we start testing kids who weren’t in school during quarantine, thereby assuming they had a “normal” education. But we have to wait for those kids to be born, grow up, and hope that there’s still an agency left standing to test them. This gives us some time to instead ask if, maybe, there could be, perhaps, just potentially, some structural causes for kids becoming dumber, year over year, before our very unblinking eyes, with little intervention being done by the powers who supposedly have their best interests in mind. And, maybe, these structural problems don’t just put their roots into the present, the last 10, or the last 20 years, but rather reach much further back in US history.

One of my hobbies is reading books that slant towards what you’d find on a library technician program’s reading list, the theory of learning and teaching. I try to keep up on educational outcome statistics, but I never really felt a need to learn the history of education in the US. To confess to my ignorance, I just never wondered “why?” I know that there was desegregation; I, too, saw Remember the Titans. But, I don’t really know what was done outside of what I was taught in a US history class, which is to say that I don’t know much. I know that there’s a Department of Education, but not that it, as a limb of the body of government, is younger than the Cuban Missile Crisis*. And, most importantly, I don’t really know how any single facet of US history factors into the idea of literacy in the modern day. And the sources just don’t help.

*I suppose you could say there was a DoE in 1867. Four guys doing data science in a broom closet, who made it less than one calendar year before the body’s dissolution in 1868.

Caption: “Just clocking in, boss.”

It’s easy to find factoids and articles about the history of education in the US, but literacy, to me, is more than that. When America administered literacy tests in order to vote, that wasn’t just a test of whether or not you could read, how you were educated, if you were educated, it was a clear statement that literacy was one of the barriers of entry for political involvement in America*. When I say I want to learn why we find ourselves in our current position, I am not just interested in the raw history, but rather the politics of literacy. When I went online to try to find something, anything, to satisfy my curiosity, I came up empty-handed in the answer to one question or another. I find sources on what was done, but not how. I find the how, but I miss the reactions, the names, the places, the dates, and this frustrates me. Maybe, after years of ring-rust, I’m just a bad researcher, or maybe this isn’t a question that others have found fruit in asking.

*It was also a way to “legally” prevent non-white people from voting. Worth explicitly noting here. We’ll wheel around to that later on.

But I have a fear, one that creeps up from the recesses of my mind when I visit a college campus, see right-wing reactions to the Common Core system, or when the word “retrenchment” enters stage left. It’s a combination of algorithmically-induced brain poisoning and a love for my neighbors, as well as a product of my cynicism, that there’s a growing sentiment among those who lead our educational institutions that this answer just doesn’t matter; there’s no money to be made in building schools, for example, when you can instead make the school profitable. Private investors, educational corporations, and textbook publishers, meanwhile, gnaw at the paint, worm into the drywall, and fuck off with their spoils, with their board members’ names scrawled in the viscera they leave behind. In schools across the country, the walls turn grey, the books cake with dust, and if something doesn’t give, there won’t be a soul inside to teach.

I try to have hopes, too. I want to write about the politics of literacy because, for some reason, I hope that there’s other people out there who care, people who want to try to know just what the hell is going on.

If you made it this far, hopefully that means that you have those hopes, too.

This is the start of a series of indeterminable length. If you enjoyed reading, please subscribe so that you can see more of what I write. It’s free!

References

https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/ltt/?age=9

https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/reports/reading/2024/g4_8/?grade=8